https://www.economist.com/node/21798232?fsrc=rss%7Cbus

TWO AMERICAN giants, spooked by a crisis that has roiled oil markets, fall into each other’s arms. The tie-up strings back together bits of Standard Oil—broken up in 1911 in the world’s most famous trustbusting exercise. The year was 1999, and Exxon had just completed an $81bn merger with Mobil. Might history repeat itself in 2021? The world of corporate dealmaking is abuzz following reports that last year the bosses of ExxonMobil and Chevron discussed combining the two firms, clobbered by covid-19 along with the rest of their industry. The talks are off, apparently. But they could be rekindled. The resulting crude-pumping colossus could produce enough to meet over 7% of global oil demand.

This time, though, the deal would not be a show of strength, especially for ExxonMobil. The company was under strain before the pandemic. Despite a $261bn capital-spending splurge between 2010 and 2019, its oil production was flat. Its net debt has ballooned from small change to $63bn, in part to maintain its sacrosanct dividend, which costs it $15bn annually. The company, which had a market capitalisation of $410bn ten years ago—and in 2013 was the world’s most valuable listed firm—is worth less than half that now. In a symbolic blow, last August it was ejected from the Dow Jones Industrial Average, after 92 years in the index.

Adding injury to insult, on February 2nd ExxonMobil reported that a decade of gushing profits—which averaged $26bn a year between 2010 and 2019—had come to an end. The firm booked its first-ever annual net loss, of a staggering $22bn. Much of that was a one-off write-down of natural-gas assets. ExxonMobil is not the only oil firm suffering; Britain’s BP also announced an annual loss this week. Darren Woods, ExxonMobil’s chief executive, gamely argued that the firm was “in the best possible position” to bounce back. As rivals have talked about a new future of renewable-energy investment, Mr Woods has been frank about doubling down on hydrocarbons. His firm’s strategic mantra is that demand for fossil fuels will remain high for decades as consumers in emerging markets buy more cars, air-conditioning units and aeroplane tickets.

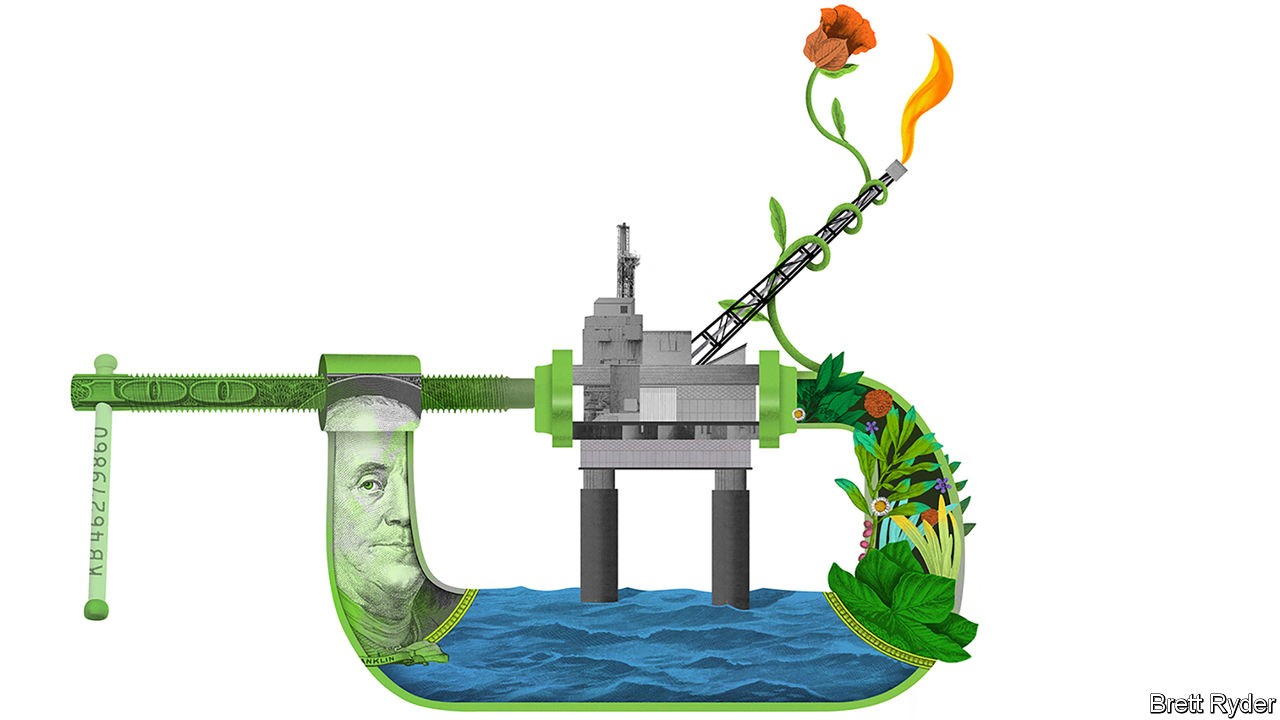

Shareholders are no longer so sure. Those concerned about greenery are angered by ExxonMobil’s continued carbon-cuddling. Those who care more about greenbacks are irked by its capital indiscipline. Right now, both are pushing in the same direction.

D.E. Shaw, a big hedge fund, is urging ExxonMobil to spend more wisely. The company’s return on capital employed in exploration and production fell from an average of over 30% in 2001-10 to 6% in 2015-19. The fund has urged Mr Woods to be more like Michael Wirth, his opposite number at Chevron, who has focused more on value and less on volume. More eye-catchingly, Engine No.1, a newish fund with a stake of just 0.02%, is trying to green-shame Mr Woods with a mantra as straightforward as ExxonMobil’s: if the company continues on its current course, and demand shifts quickly to cleaner energy, it risks terminal decline. The fund has launched a proxy battle by proposing four new directors; the current board, it complains, is long on blue-chip corporate credentials but short on energy expertise. Engine No.1’s agitation for a shake-up has won backing from, among others, CalSTRS, which manages $283bn on behalf of California’s public-sector workers.

Most important, the tone from ExxonMobil’s three biggest institutional shareholders—BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street—has also shifted. Between them these titans of asset management own around 20%. That understates their power. Many retail shareholders who own the company’s stock directly do not bother to vote, leaving the big guns that do with outsized sway. Where once asset managers occasionally wagged a finger at climate-unfriendly firms, they are starting to threaten to walk away.

In a recent letter to clients, Larry Fink, boss of BlackRock, talked of greener stocks enjoying a “sustainability premium” and dirty ones jeopardising portfolios’ long-term returns. He hinted that his firm—the world’s largest asset manager—might divest from firms that failed to appreciate the “tectonic shift” taking place. Vanguard, too, has called out ExxonMobil for flawed governance.

Such badgering used to fall on deaf ears. Now, ExxonMobil seems ready to make some changes. It has just added the ex-boss of Petronas, a Malaysian energy group, as a director, as part of a “board refreshment”. It also unveiled a $3bn effort to intensify its work on carbon capture. The firm is paring back spending on new rigs, and narrowing its focus to higher-return fields in places like Guyana and to America’s Permian shale basin.

Texas let ’em go

This is a start. But it looks unlikely to appease increasingly restive shareholders. Some of the green-minded rebels think ExxonMobil is too focused on carbon-capture technology, which is costly and has yet to be deployed at scale by anyone who has tried, and not focused enough on reducing emissions. Unlike many peers, the firm has set targets for bringing down only the intensity of emissions from its operations, not their overall level—leaving room for more belching if production rises. It lags behind rivals in targeting “scope 3” emissions: those of customers burning its petrol and jet fuel. ExxonMobil may also have to offer further concessions to those shareholders who fret more about capital than carbon. A big cut in capital spending in 2020 has gone down well, but its planned annual outlay of $20bn-25bn in coming years still looks splashy compared with that of parsimonious rivals.

The firm’s response “has only emboldened us”, says a member of Engine No.1’s proxy-fight team. “They are still looking at the world today, or in five years, not the long-term trajectory—which is exactly what got them into this mess.” Last year Mr Woods survived a shareholder resolution, backed among others by BlackRock, to strip him of his dual role as ExxonMobil’s chairman. This time around, as Davids and Goliaths gang up on him, the oilman may be less lucky.■

For more coverage of climate change, register for The Climate Issue, our fortnightly newsletter, or visit our climate-change hub

This article appeared in the Business section of the print edition under the headline “The long squeeze”