https://www.economist.com/node/21802662?fsrc=rss%7Cbus

CHENG WEI, the billionaire founder and chief executive of Didi Global, had scarcely a moment to revel in his firm’s $4.4bn New York listing. Within 48 hours of the initial public offering (IPO), which valued the Chinese ride-hailing giant at around $70bn, regulators in Beijing spoiled the party. On July 2nd the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) said it had launched an investigation into the company. The announcement shaved 5% off its share price.

Two days later the regulator ordered Didi’s mobile app to be pulled from app stores in China, halting new customers from joining the service (existing users can still hail taxis). The CAC alleges that Didi was illegally collecting and using personal data. Didi said that it would “strive to rectify any problems” but warned of “an adverse impact on its revenue in China”. Predictably, the ban also adversely affected the company’s market value. When American markets reopened on July 6th, Didi promptly shed more than a fifth of it. It is now worth $22bn less than a week go.

The CAC’s move is an escalation in China’s crackdown on big technology firms. On July 5th it told three other apps—Yunmanman and Huochebang, which operate lorry-hailing and cargo apps, and Boss Zhipin, an internet recruitment service—to stop enlisting new users. The trucking services, which merged under the name Full Truck Alliance, and Kanzhun, which owns Boss Zhipin, had together raised $2.5bn in American flotations last month.

Wolf warrior of Wall Street

All told, Chinese firms have raised $13bn in America so far this year, and $76bn over the past decade. Around 400 Chinese companies have American listings, roughly twice as many as in 2016. In that period their combined stockmarket value has shot up from less than $400bn to $1.7trn. Those investments are now in peril. On July 6th Chinese authorities said they would tighten rules for firms with foreign listings, or those seeking them. It is the starkest effort yet to disconnect China Inc from American capital markets.

Besides regulating what corporate data can and cannot be shared with foreigners, the new rules would target “illegal securities activities” and create extraterritorial laws to govern Chinese firms with foreign listings. According to Bloomberg, a news service, Chinese regulators also want to restrict the use of offshore legal structures that help Chinese companies skirt local limits on foreign ownership.

Nearly all Chinese tech giants listed in America, including Alibaba, a $570bn e-merchant, as well as Didi, use such “variable-interest entities” (VIEs). A VIE is domiciled in a tax haven like the Cayman Islands, and accepts foreigners as investors. It then sets up a subsidiary in China, which receives a share of the profits of the Chinese firm using the structure. China’s government has long implicitly supported this tenuous arrangement, upon which hundreds of billions of dollars of American investments rely. Now it wants Chinese firms to seek explicit approval for the structure. The assumption is that Beijing would be hesitant to grant it. Existing VIEs may also come under scrutiny.

A formal blessing from Beijing may help avoid the sort of kerfuffle Didi has found itself in. In April the firm was among 30 companies called in by the CAC and the State Administration of Taxation. It was given a month to conduct a sprawling self-inspection. It added a warning that it “cannot assure [investors] that the regulatory authorities will be satisfied with our self-inspection results” to the risks listed in its prospectus, alongside antitrust, pricing, privacy protection, food safety, product quality and taxes. It went ahead with its New York IPO regardless. Punishing the company right after its listing looks like deliberate retaliation for pressing on before the regulators were done with their probing, says Angela Zhang of the University of Hong Kong. Didi’s new public investors were badly burnt as a result, just as the private investors in Ant Group were in November, when the financial-technology firm’s $37bn IPO was suspended two days before its shares were due to begin trading in Hong Kong and Shanghai.

All this is chilling both Chinese firms’ appetite for foreign listings and foreign investors’ hunger for Chinese stocks, and not just in America. The day after the Didi ban the four biggest tech groups with listings in Hong Kong—Tencent, Alibaba (which has a dual listing), Meituan and Kuaishou—lost a collective $60bn in market capitalisation. The effects on some of the world’s most innovative and value-generating companies of the past decade may be crippling, especially in conjunction with greater scrutiny of Chinese companies by America’s government.

American regulators have long sought to force Chinese companies listed on America’s bourses to submit auditing documents to an oversight body called the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board. In December Congress passed a law that would require such disclosures with bipartisan support. At the same time, Chinese regulators have refused to permit Chinese companies to make such disclosures, declaring auditing documents to be state secrets. If the standoff does not ease, Chinese groups could eventually be forced to delist from America.

So far there is no sign of easing. Before Didi’s IPO, Marco Rubio, a Republican senator from Florida, called on America’s Securities and Exchange Commission to block the transaction. He fumed that the flotation “funnels desperately needed US dollars into Beijing and puts the investments of American retirees at risk”. This week he called the decision to let the IPO go ahead “reckless and irresponsible”. President Joe Biden is less strident but his Democratic Party also wants to curb China’s economic and technological might.

As the symbiotic relationship between Chinese firms and American investors unravels, both will suffer. The former are losing access to the world’s deepest capital markets, the latter to some of its hottest stocks. The market value of Chinese firms in America has fallen by 6% since the Ant debacle last autumn signalled a shift of mood in Beijing, even as the S&P 500 index of big firms has gained 30% as a whole. Didi won’t be the last casualty. ■

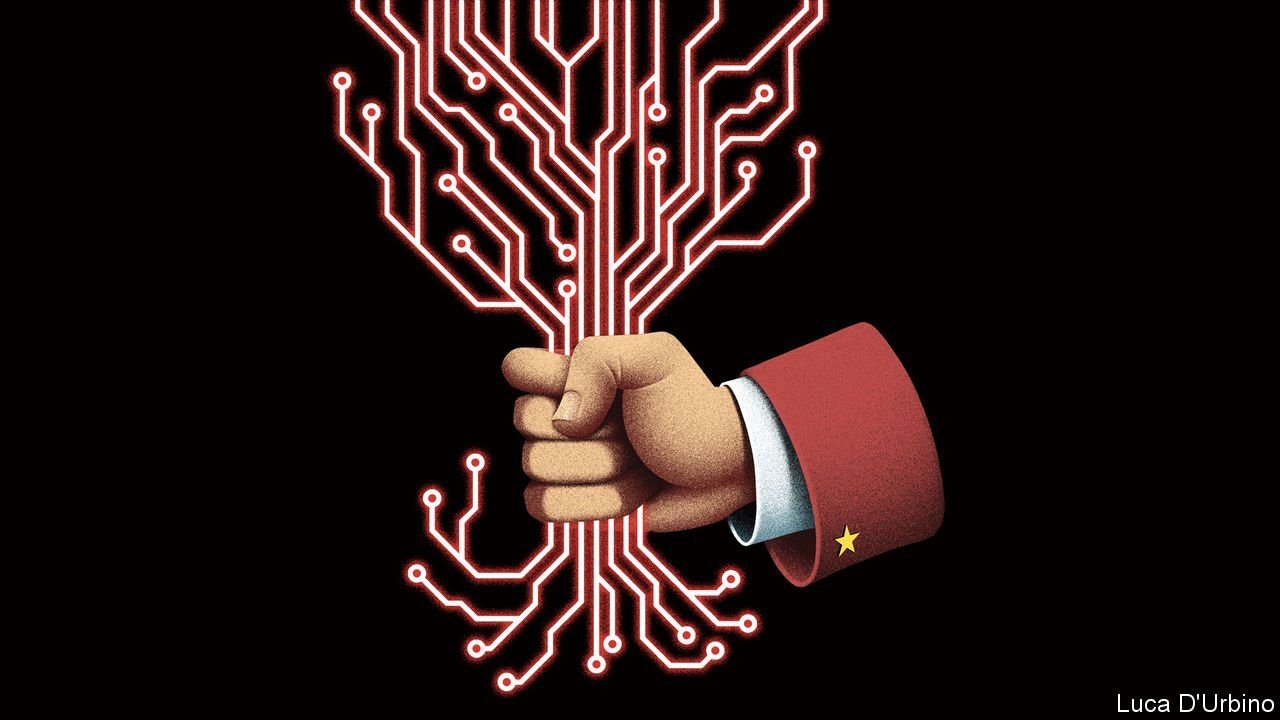

This article appeared in the Business section of the print edition under the headline “In the grip of anxiety”