https://www.economist.com/node/21802986?fsrc=rss%7Cbus

ANTITRUST USED to be as American as apple pie. The Boston Tea Party was, in part, a protest against the monopoly of the British East India Company. The word itself stems from the trusts, such as Standard Oil, that lorded it over the American economy in the 19th century. For stretches of the 20th it became America’s charter not just for free enterprise, but for political freedom. Contrast this with China, a Communist dictatorship whose AntiMonopoly Law, introduced in 2008, has more often than not been used only to cudgel foreign firms. In such hands, it is easy to dismiss trustbusting as Orwellian gobbledygook.

And yet suddenly antitrust in China has come to life in the way police internal affairs have done thanks to the British cop show “Line of Duty”: as a source of unending fear and fascination, carried out by agencies with impenetrable acronyms and a keenness for Stasi-like dawn raids. In short order, it has transformed the country’s erstwhile tech giants into simpering poodles.

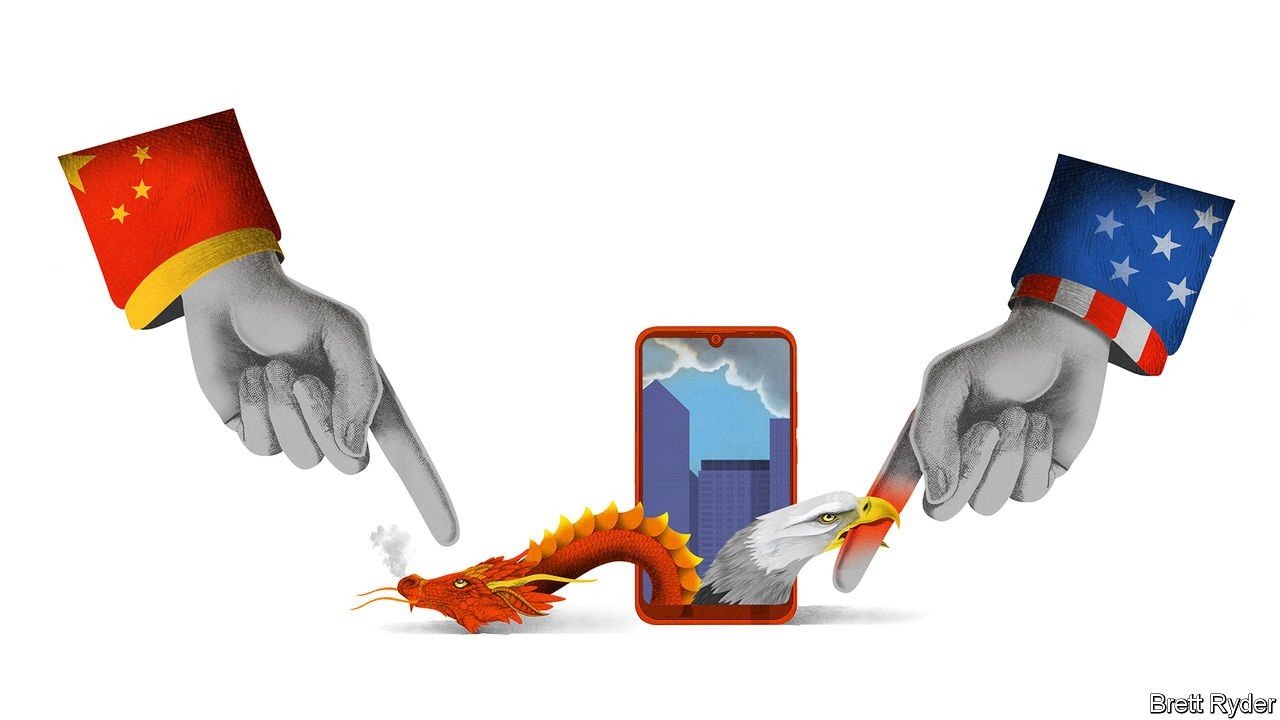

The onslaught marks the rise of a new sort of regulatory authoritarianism. Both America and China have similar qualms about the influence of their big technology firms. But since President Xi Jinping gave the nod to his trustbusting warriors last autumn, China has leapfrogged America in the speed, scope and severity of its antitrust efforts, giving new impetus to the word “techlash”. For those frustrated at the power of the tech giants in America, China offers a masterclass in how to cut them down to size. If only, that is, America could emulate it.

Start with speed, the Communist Party’s biggest edge over America’s democratic ditherers. When overweening tech barons treat politicians like patsies, don’t invite them to mind-numbing congressional hearings. Force them to keep a low profile for a while, as China did with Jack Ma, co-founder of Alibaba, China’s biggest e-commerce firm, who also founded its fintech stablemate, Ant Group. In no time, the billionaire class got the message. It took just over six months after the humbling of Mr Ma for the founders of two other Chinese tech giants, Pinduoduo and ByteDance, to announce they were retreating from public life. It also took less than four months of antitrust investigation for Alibaba to be clobbered with a $2.8bn fine in April. By contrast, a trial date for Google, sued last October by America’s Department of Justice (DoJ) and 11 states for alleged monopolistic abuse by its search business, will not come before 2023. Yawn.

Next, scope. Don’t let pesky courts stand in your way, as they do in America. Throw the book at mischief-makers using whatever tools a one-party system affords you. As Angela Zhang puts it in “Chinese Antitrust Exceptionalism”, a book written before the latest tech crackdown, Chinese regulation of monopolies starts with agencies jostling for power and influence. Their recent rampage has been supercharged by modified laws in an array of subjects. They have slapped fines on firms for crimes ranging from online price discrimination to merchant abuse and irregularities in tech merger deals. The recent crackdown on Didi, a ride-hailing giant, days after its initial public offering in New York, focuses on concerns encompassing data security and spying.

Do not expect Didi, or the alleged monopolists, to seek protection from the courts. In China trustbusters are almost never subject to judicial checks and balances. Chinese agencies, writes Ms Zhang, handle “investigation, prosecution and adjudication”. In other words, they are police, judge and jury rolled into one. In America the reverse is true. In June an American judge threw out a six-month-old lawsuit by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), America’s antitrust regulator, against Facebook, arguing that the government never proved that the social network had monopoly power. Round two to the totalitarians.

Third, severity. It isn’t the fines tech titans fear most. It is having their business models torn apart, as Ant’s was, as well as the reputational damage; bureaucrats can use state media and populist outrage to wreak havoc on a miscreant’s sales and share price. This year, amid the crackdowns, the value of China’s five biggest internet firms has plummeted by a combined $153bn. In America, despite lawsuits, probes and hearings, the value of Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Microsoft has soared by $1.5trn. As Chinese firms capitulate, American ones fight back, publicly challenging their antagonists, such as Lina Khan, who heads the FTC. Jonathan Kanter, President Joe Biden’s Google-bashing pick to run the DoJ’s antitrust division, can expect similar treatment.

Be careful what you wish for

Presumably all this would arouse envy among trustbusters in Washington, DC—were “China” not an even dirtier word than “tech” these days. Not only has China taken up the antitrust mantle from its superpower rival. It has done so strategically. It strengthens Mr Xi’s control over potential rivals for popular adulation: the tech billionaires. It gives the central government more oversight of an ocean of digital data. And it encourages self-reliance; the aim is to have a thriving tech scene producing world-beating innovations under the thumb of the Communist Party.

But autarky carries its own risks. Already, Chinese tech darlings are cancelling plans to issue shares in America, derailing a gravy train that allowed Chinese firms listed there to reach a market value of nearly $2trn. The techlash also risks stifling the animal spirits that make China a hotbed of innovation. Ironically, at just the moment China is applying water torture to its tech giants, both it and America are seeing a flurry of digital competition, as incumbents invade each other’s turf and are taken on by new challengers. It is a time for encouragement, not crackdowns. Instead of tearing down the tech giants, American trustbusters should strengthen what has always served the country best: free markets, rule of law and due process. That is the one lesson America can teach China. It is the most important lesson of all. ■

This article appeared in the Business section of the print edition under the headline “War war v jaw jaw”